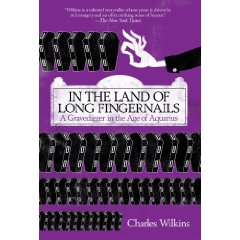

In the Land of Long Fingernails: A Gravedigger in the Age of Aquarius isn’t a work of fiction, but with such a setting and characters like this, Charles Wilkins’ memoir reads as well as one.

In the Land of Long Fingernails: A Gravedigger in the Age of Aquarius isn’t a work of fiction, but with such a setting and characters like this, Charles Wilkins’ memoir reads as well as one.

In the summer of ’69, Wilkins took a job at a cemetery. The gig alone would be worthy of many stories — and they are in there, believe me — but being a memoir, Wilkins focuses on the people in the place. This may, to some, seem a bit silly — like he’s ignoring the, umm, meat of the situation. Especially when the inside flap of the dust jacket says, “Hardly a day passed that Wilkins did not witness some grim new violation of civility or law, or discover some unexplored threshold in his awareness of human behavior.” But by letting the gross and the grisly, the physical and emotional disturbances, be the backdrop for the stories for what living humans do to and for one another, Wilkins presents the reality of life lived in contrast with death that literally surrounds it. A reality most of us manage to avoid as blithely as we avoid becoming a gravedigger.

Mostly a group of manly-men who hide their lots in life, these gruff men grumble their intolerance of one another and complain about their labor; on the surface they are seemingly oblivious to their proximity to death and loss. But beneath this noise, it’s clear they are aware and questioning… They open coffins to take peeps inside, debate philosophy, and view the pomp & ceremony of religion as a capitalistic endeavor more than comforting faith. Who can blame them? But there’s also a certain poetry to this rag-tag lot of misfits too; from page 93:

“If there were such a thing as a soul, Wilkins, can you imagine what this kind of experience would do to it?” He glances upwards, taps his fingers on the coffin top.

“Wilkins,” he says, baiting me gently, “maybe there’s a soul, and it lasts only as long as the body.”

“And then what?”

“It becomes a story,” he says

Among the big issues of life and death, The Land Of Long Fingernails is a memoir and as such holds the coming of age story of the college-aged Wilkins; in light of all the gruesome, Wilkins grew some.

Readers can too.

In terms of the writing itself, there is one bump. Frankly speaking, the first nine paragraphs of chapter two should have been been the start of chapter one. Getting a close-up of the very real (yet renamed to protect the author and the not-so-innocent) Willowlawn Everlasting cemetery, only to be moved backward for the establishing shot of the 60’s culture was jarring. Rather like stumbling up a staircase, you eventually reach your destination, but really, did you need to be so startled? Fortunately, we recover quickly and Wilkins never makes such a mistake again.

The repellent realities of nature and the “Oh. My. Gawd. That’s unreal!” human actions (be they the repugnant human hypocrisy or cold calculating illegalities) are shocking — but neither they, nor the folks buried underground, are more powerful than the stories of the humans which dig, sculpt, and stamp about living upon the surface.

If Halloween is supposed to be the time at which we explore the veil between the living and the dead, then now is the perfect time to read In The Land Of Long Fingernails; however I wouldn’t limit the book so seasonally. A highly recommended read.